Chapter 3, Part 2 — AI & Instruction

AI is starting to support teachers by automating prep and grading—but it also raises real concerns about burnout, overreliance, and losing the human touch in the classroom.

Chapter 3, Part 2 — Applying AI to Education

AI & Instruction

“What the teacher is, is more important than what he teaches.” — Karl Menninger

Already, cutting-edge AI researchers and EdTech developers are heralding the benefits of using AI in instruction. Vasiliy Kolchenko, in his 2018 research article Can Modern AI Replace Teachers?, argues that AI holds the potential to achieve the ultimate goal of education: to provide personalized, wise, and attentive guidance for each student (Kolchenko, 2018). According to Kolchenko, AI could tailor learning materials and activities to match the unique pace and learning style of each student.

On the other hand, Derrick Li, the founder of Squirrel AI—one of China's largest AI education companies—takes a more extreme view. He suggests that AI should replace traditional teaching roles to prevent the mishandling of potentially gifted students, arguing that relying on traditional methods could “risk damaging geniuses” (Hao, 2019).

AI as a Teacher’s “Assistant”

A teacher’s job is notoriously thankless and complex, with many of their duties falling outside the boundaries of instruction such as grading, communicating with parents, and doing other administrative work (Hardison, 2022).

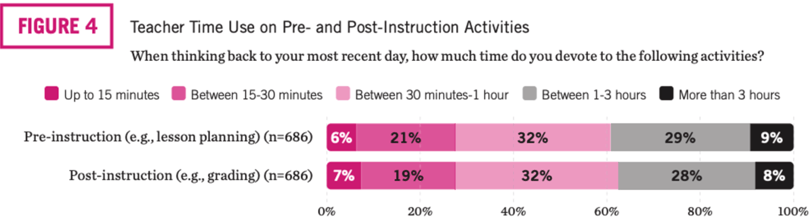

In 2022, researcher and ex-teacher Michael McShane partnered up with Hanover Research to conduct a Qualtrics survey among teachers about how much time they spend on various tasks. This survey was answered by 686 teachers K-12 across the United States with ethnicities that were close to the national average, (White and black teachers were only slightly overrepresented in the sample.) The survey found that most teachers spent between 30 minutes to an hour per day on both pre-and post-instruction work such as lesson planning or grading — based on their recollection of time spent the day before they took the survey (McShane, 2022). While over 1⁄3 of teachers spent over 2 hours/day on both pre and post-instruction combined, (between 1 & 3 hours combined), only a small percentage spent less than 30 minutes/day — with the majority of teachers (approximately 60%) reporting they spend between 1 hour and 6 hours on combined pre & post instruction each day (McShane, 2022). Needless to say, the large majority of K-12 teachers spend a considerable amount of time putting together lesson plans, grading papers, and other administrative functions that activities are not in-class instruction.

Figure 4: Breakdown of How Teachers Spend their Time (McShane, 2022).

In addition, a literature review by Reem Hashem et al. (2024) showed that much of the critical evidence supports the claim that teaching is demanding and can cause burnout due to various tasks and expectations. Therefore, one of the most exciting uses for AI in education is its potential to help teachers spend more time with students, actually teaching and engaging, while spending less time on non-instructional tasks that contribute to burnout. AI tools such as MagicSchool, Lesson Plan AI, and Eduaide.Ai already assist in creating lesson plans, enabling teachers to fine-tune them for engagement rather than building them from scratch.

With AI’s increasing ability to take on more mundane tasks, such as assessing student work or planning lessons, teachers will likely feel less overwhelmed and have more energy to focus on meaningful instruction.

Potential Perils of AI in Instruction

One of the main concerns with integrating too much AI into educational settings, including instruction, is the potential for overreliance on computer systems. This could undermine both critical thinking and diminish communal interactions that are essential to early mental and social development (Dergaa et al., 2024).

If educators do not recognize their crucial role in guiding the use of AI in the classroom, they risk giving too much control to these systems, potentially undermining the human element that is essential for effective teaching (U.S. Department of Education, 2023). Supporting this concern, research indicates that teachers themselves see the need for more training in new educational technologies. In discussions about challenges with technology implementation, many teachers have noted that additional training would benefit both themselves and their students (Carstens et al., 2021).

References

References

Hardison, H. (2022, April 19). How teachers spend their time: A breakdown. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/how-teachers-spend-their-time-a-breakdown/2022/04

Hashem, R., Ali, N., El Zein, F., Fidalgo, P., & Abu Khurma, O. (2024). AI to the rescue: Exploring the potential of ChatGPT as a teacher ally for workload relief and burnout prevention. Research & Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 19. https://rptel.apsce.net/index.php/RPTEL/article/view/2024-19013

Hao, K. (2019, August 2). China has started a grand experiment in AI education. It could reshape how the world learns. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/08/02/131198/china-squirrel-has-started-a-grand-experiment-in-ai-education/

Jasanoff, S. (2010). States of knowledge: The co-production of science and social order. Routledge.

Kolchenko, V. (2018). Can modern AI replace teachers? Not so fast! Artificial intelligence and adaptive learning: Personalized education in the AI age. HAPS Educator, 22(3), 249–252.

McShane, M. Q. (2022, July 18). How much time do teachers spend teaching? EdChoice. https://www.edchoice.org/engage/how-much-time-do-teachers-spend-teaching/

U.S. Department of Education. (2023). Artificial intelligence and the future of teaching and learning: Insights and recommendations. Office of Educational Technology. https://tech.ed.gov/ai/

Carstens, K. J., Mallon, J. M., Bataineh, M., & Al-Bataineh, A. (2021). Effects of technology on student learning. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 20(1), 109–114.